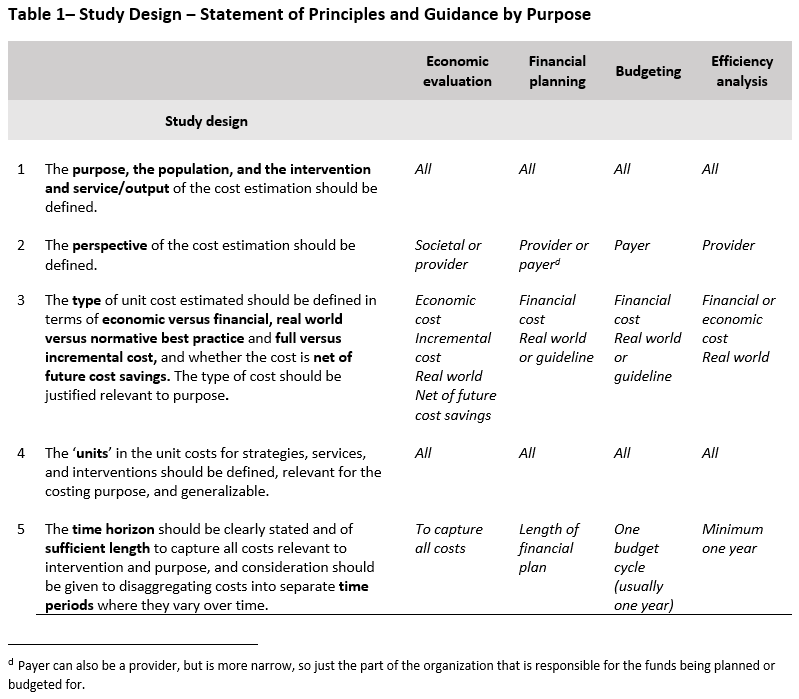

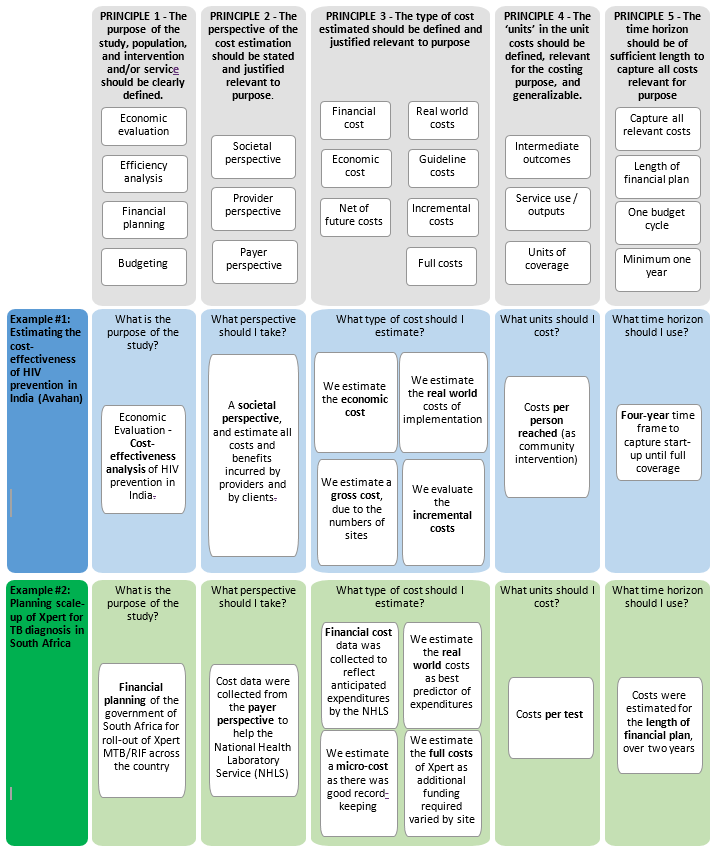

Once the purpose has been determined, this section outlines the five principles and methodological specifications relevant for study design. The various steps/choices to be made when designing a cost estimation are outlined in the diagram below. A summary of the principles to be applied in each step is also provided in Table 1. Table 1 also includes guidance on how study design may be influenced by the purpose of study and the availability of data. A statement of each principle and its methodological specifications follows the summary table.

As outlined in the introduction of the Reference Case, cost estimates may be used for multiple purposes, and the characteristics of a ‘sufficient estimate’ will vary accordingly. For example, an economic evaluation may require an incremental economic cost, while financial planning may require a financial cost from a specific payer’s perspective. If a cost estimate is used for the wrong purpose, or if its limitations are not described, it can be misleading. Therefore, it is important to be clear on the purpose for which the cost estimate is intended.

The requirement that the population and intervention and/or service/outputs be clearly described complies with standard economic evaluation guidelines, such as the US Panel recommendations and the iDSI Reference Case14. This information is essential for costs to be used appropriately and generalized to other settings, and provides the basis for determining the methods used for measurement.

The introduction of the Reference Case provides examples of purposes that may be used. These are: economic evaluation, efficiency analyses, financial planning, and budgeting. The purpose should also identify both the relevance for health practice and policy decisions and the intended user(s) of the cost estimate, if known.

Ideally the intervention and/or service/output should be defined within context describing:

- Main activities/technologies involved

- Target population

- Coverage level or phase (pilot, implementation, post scale up)

- Delivery mechanism (health system level/facility types/community/ownership /integration with other services where relevant)

- Epidemiological context (incidence/prevalence of the illness being addressed)

The comprehensive production process of an intervention and/or service/output (i.e., the activities, plus key technologies) should be outlined in the first instance, and if any parts of process are excluded (for example above service delivery activities) these exclusions should be clearly reported.

Once a purpose and user of the cost estimate is defined, it is important to address the perspective of the estimation. The perspective describes which payers’ costs are included in the estimate. Some users, who make decisions on behalf of a population, may need to use a societal perspective that captures all costs incurred by an intervention, regardless of who pays the costs. For other analyses, a more limited perspective may be taken. For example, to set a budget, it may only be important to estimate the costs that fall on a specific payer.

The requirement that the perspective should be described complies with standard economic evaluation guidelines, such as the US Panel14 recommendations and the iDSI Reference Case13. There are increasing calls for economic evaluations to adopt a societal perspective, including the recent recommendation by the Second US Panel to report two Reference Cases, one from a provider and one from a broader societal perspective22.

Most textbooks in costing and economic evaluation categorize perspective into two types: societal and provider. However, in practice, these terms are used to describe a multitude of payers. For example, a provider perspective may include costs incurred by health service providers and non-health service providers, and be limited to specific payers. A societal perspective may also include client costs to access a service, costs to the household, costs to community, and in some cases even costs to the macro-economy or other sectors. Where clients or patients pay for services, the costs of provision may include a partial societal perspective. Therefore, a simple category stating the perspective as societal or provider is insufficient to generalize or compare costs. It is therefore recommended that a ‘stopping rule’ be defined and made explicit. A ‘stopping rule’ defines and explains which costs are included, and how the line is drawn between inclusions and exclusions.

The methodological specification is therefore to define perspective as societal or provider, but in addition to justifying and listing the groups/payers whose cost has been captured in the estimate. For a provider perspective, this should specify whether both health and non-health providers are included. For a societal perspective, this should specify whether it is cost to the client only, or more broadly to the household, community, or society.

For different purposes, different types of costs are required. For example, economic evaluation requires an incremental economic cost to ensure opportunity cost is appropriately estimated13. Conversely technical efficiency analyses may be interested in examining the full cost, to identify any possible resource use that is inefficient. Different types of costs will require different measurement methods, and for reasons of measurement design and comparability, it is important to begin any cost estimation process with a clear definition of what cost is being estimated.

There are four characteristics that must be defined. First is the distinction between economic and financial cost (see introductory text and glossary). Whether the cost is economic or financial will dictate which resources should be included and how they should be valued.

The next issue is whether the aim is to estimate the cost of an intervention conducted according to ‘normative best practice’, or whether the aim is to provide a cost estimate that reflects the costs of implementing an intervention in the ‘real world’ (which may include inefficiencies or exclude intervention components). Normative best practice may be described in guidelines, but guidelines may be out of date and expert consultation may be used. In most cases, this will also be a mixed picture, not a dichotomy, with some aspects of the ‘real world’ being included, but not all. For example, normative best practice may be defined as ideal norms, or have more realistic elements.

The setting where costs are collected may be pivotal. For example, where costs are collected in research settings they may be gathered from clinical trials or more pragmatic settings. Costs for economic evaluation are often collected from clinical trial sites, where the cost may include activities to ensure adherence to a guideline, which may also contribute to the effect size used in the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) estimation. In this case is important to be clear that the costs include activities to ensure guideline adherence. It is therefore necessary to provide more detail than simply stating whether the cost is real world or based on guidelines. Given the complexity involved, transparency around this issue is particularly important.

It is also important to clarify whether the cost estimate is incremental to any comparator or a standard of care. The definition of incremental is outlined above in the introductory section. Further guidance on defining resources to be included in cost estimates is provided in methodological specification six below.

Finally, many global health interventions are preventative, and therefore it is important to report whether costs are net of future cost savings for health providers and households or just the costs of the immediate intervention.

A critical challenge in transferring and synthesizing cost estimates in the past has been the lack of standardized ‘units’ costs for interventions, episodes of care, and service usee. This lack of standardization has created difficulty in assessing efficiency across settings, made past and existing efforts to conduct systematic reviews problematic, and impeded the creation of global datasets of costs that can be used to extrapolate costs to settings where data is currently absent. A key aim of this Reference Case is to address this gap by developing a standardized set of units for different disease and intervention areas.

The introduction section above describes the categories of unit costs that may be defined (strategies, intervention and service units). As part of this Reference Case we also provide examples of standardized units for TB, based on the ‘units’ of strategies, services, and interventions that countries are reporting activity on globally, in Appendix 2. There is also guidance available in other areas, such as immunization, often developed in conjunction with global agencies working in specific areas. These can be found on the GHCC website: https://ghcosting.org/

In all cases these units should be reported, although in some circumstances it may be relevant to report additional units. For new interventions, or interventions with new components, other units may need to be developed beyond the standardized unit costs in this Reference Case. In some cases, the management information systems that report on the various ‘units’ will not align with the standard definitions; if this is the case, effort should be taken to collect the necessary additional data to adjust this reporting, or clearly explain any bias in terms of standardized reporting units.

Finally, a critical issue to consider is the use of quality-adjusted ‘units’. This is particularly the case for purposes that are examining efficiency. Comparing costs of services that are of varying quality and thus different is misleading. To explore efficiency, analyses may therefore want to examine the factors that influence the cost of services reaching a similar quality. For example, the purpose of the costing may require that the cost per person completing treatment, rather than the cost per treatment month, is explored. In other cases, the analysis may also consider quality as a determinant of costs. Even if not formally analyses, in all cases, efficiency analyses should consider the quality of the output, in any inference made from these analyses.

For other purposes, quality may be less critical to explore. For example, in cost-effectiveness analysis, the main metric is cost per outcome, and thus a decision may require also knowing the cost per quality adjusted output. For financial planning and budgeting, ideally the quality of the service being budgeted for should be clearly defined as part of the intervention definition, and ‘unit’ costs then measured accordingly.

Time horizon refers to the length of time of service provision or intervention implementation that the costs are being considered. While most unit costs are contained by the length of time it takes to provide the service or produce an output (for example, TB treatment is six months), there are other considerations depending on what costs are being estimated and the purpose of the analysis.

In economic evaluation, it may be necessary to estimate a unit cost of an intervention per person (see box 2 above). In this case the time horizon may have to capture multiple services over time. The iDSI Reference Case for Economic Evaluation14 states that time horizon used in an economic evaluation needs to be carefully considered because any decision made at a point in time will have intervention benefits and resource use extending into the future. An economic evaluation should therefore use a time horizon that is long enough to capture all costs and effects relevant to the program or policy decision. Economic evaluation Reference Cases and guidance more generally emphasize that the time horizon should not be limited by the availability of empirical data. In some cases, however, it is not possible to measure future costs and economic evaluations may include imputation of data that are incomplete or missing23, with a number of analytical methods being available to address the specific issue of censored data24. Other uses of cost data may have more circumscribed time horizons related to financial planning periods.

Finally, where estimating a unit cost for new services, it may make sense to disaggregate unit costs into different time periods. Costs may change during different phases of an intervention, and therefore an average unit cost over the entire intervention may have limited use for other analysts using cost data for specific phases of activities, particularly in financial planning. For example, costs may be different during the development of intervention, compared to implementation.

For costs estimated for economic evaluations the time horizon should follow the methodological specifications in the iDSI Reference Case13. For other purposes, the time horizon should follow the planning cycle, (e.g., medium-term financial planning typically estimates costs for 3- to 5-year periods, while longer-term efforts to estimate resource needs to reach global targets may project costs for a 10- to 15-year period).

For interventions that are being piloted or at the early stages of implementation, costs should be disaggregated into those in a ‘start-up’ phase and those in an ‘implementation’ phase, at a minimum, with the start-up phase being treated as a capital investment (see principle 12 below). A start-up phase is defined as all costs incurred before the first service is delivered. For clinical services, like TB treatment or ART treatment, there may also be clinically related phases, such as intensive and continuation phases. Even within phases of treatment costs may vary, and it may be relevant to examine this in some circumstances. For example, hospital admission costs vary over the course of treatment (the first few days are often higher cost)25. For an economic evaluation comparing an intervention reducing length of stay, it may be necessary to capture this variation over days.