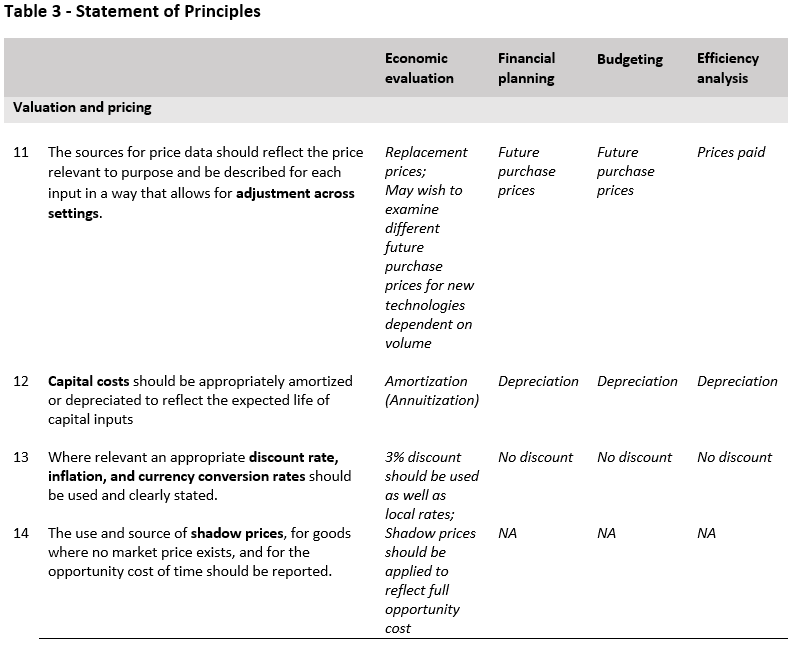

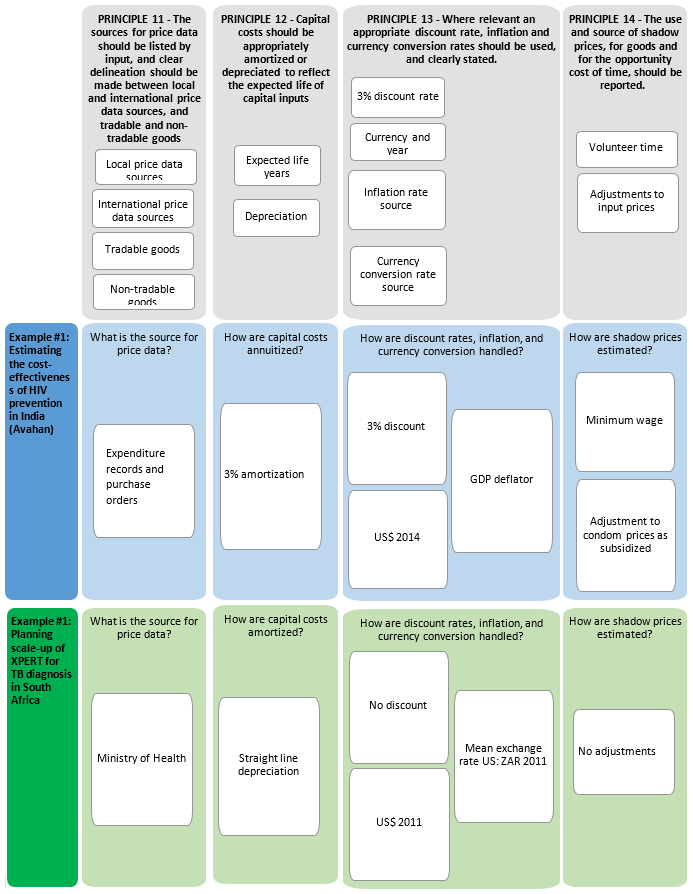

The third part of the Reference Case focuses on pricing and valuation. Four principles are defined, represented in Table 3 and in the figure at the end of the section.

Providing information on prices (including sources and methods used for salaries and wages) is a central aspect of transparency, and enables costs to be adjusted across settings with different prices. Different prices may be appropriate for different purposes. For example, financial planning and budgeting may need to estimate future costs, so contacting manufacturers of key technologies may be appropriate rather than assuming today’s prices will hold as volumes increase. There may be purchasing arrangements, which means that the prices of specific brands should be used. Efficiency analyses will need to examine the prices paid, and purchasing records may be a good source in this case. Economic evaluations may need to capture replacement prices in order to best capture current opportunity cost.

The source of price data should reflect the purpose of the cost estimation.

In some cases, some adjustments may need to be made from the price given in the original data source. For example, for wage and salary costs, adjustments may need to be made to ensure all benefits and remuneration are included and that gross price is captured. For example, efforts may need to be made to capture all the monetized benefits that public servants receive when pricing human resources. In the case of drugs and supplies, it may be appropriate to mark up prices by transportation costs.

To enable the transfer of costs across settings, it is also important to distinguish local from international price sources, and between tradable and non-tradable inputs. Non-tradable inputs will always have local prices. Tradable goods may have both a local price and a price listed on global websites, etc. Wages are an example of “non-tradable” inputs; pharmaceuticals and lab testing equipment are often “tradable” inputs. Defining inputs as tradable and non-tradable and listing their price source is required to transfer costs across settings and to convert costs, where relevant, to international dollars.

The definition of a capital cost is any input with a useful life of more than one year, and can include non-equipment inputs such as training and bed linen. Start-up costs can also be considered as capital costs, given that their usefulness is typically longer than one year.

Capital costs potentially have two components: depreciation (the reduction in the value of the asset over time due to wear and tear) and opportunity costs. The opportunity costs of capital reflect the lost opportunity to invest in another area. Even if an item of capital has been purchased some years ago, it can always be resold and still has an opportunity cost. Economic cost methods aim to capture this opportunity cost, whereas financial costs will only capture depreciation. Depending on the proportion of capital costs to total costs, differences in the method used to spread the cost over years can substantially impact unit costs77.

Capital costs should be valued according to the type of cost ‒ ‘economic’ or ‘financial’ ‒ being estimated. Financial cost estimates should use straight-line depreciation (simply dividing the total cost by the years of useful life) and economic costs should use an amortization (sometime referred to as annualization) factor that adjusts the years of life for opportunity cost. It does this adjustment using a discount rate. As stated below in Principle 13, a 3% rate should be used in all cases to allow for international comparisons to be made. If local rates are available these should always be used in addition to the 3% rate. Standard tables are available to determine this adjustment78.

The determination of the useful life of capital can also be problematic where the setting characteristics, such as the availability of repair and maintenance infrastructure, may influence the length of potential use. This is also the case for novel technologies where useful life has not yet been observed. It is therefore important to report useful life years used, even if assumption based, so that costs can be generalized and adapted to other settings and sensitivity analyses can be conducted.

In summary, the method of depreciation and capturing opportunity cost, the discount rate, and the useful life (length and data sources) should be reported for each major capital input category and for new capital technologies by input.

As above in principle 11, transparency around all adjustments to prices is essential; therefore, any adjustments made to adapt costs across setting and time need to be reported. The iDSI Reference Case for economic evaluation13 also states that when projecting costs into the future, costs need to be discounted to reflect their value at the time the decision is being made.

In line with the iDSI Reference Case, a 3% annual and the local

discount rate

for costs should be used as a minimum specification. Additional analysis exploring differing discount rates appropriate to the decision problem can also be used, depending on the purpose and end user. In many cases an analysis that reflects the discount rate using the rate at which the national government can borrow funds on the international market (i.e., the rate used by the Treasury) may be preferable as the primary estimate for national level users. In this case, an adjustment for inflation may need to be made to reflect the real rate of return.To enhance generalizability of a cost estimate as stated above, we recommend at a minimum to present costs in local and US dollars, specifying the currency year. In some cases, it may also be advisable to present results in international dollars. International dollars, using a purchasing power parity conversion, remove some of the distortions and fluctuations inherent in currency markets and may better represent ‘economic’ value. However, for purposes such as financial planning, exchange rates are likely to be better estimates of price to be paid. In most cases, it may be necessary to also present costs in local currency. Where costs are reported over a time period, the mean exchange/ conversion rate over that year or time period should be used. The source of the exchange rate should be specified.

Where prices need to be adjusted across time, gross domestic product (GDP) deflators or the Consumer Price Index (CPI) should be used for local goods (GDP deflators measure inflation in locally produced goods, rather than locally consumed goods). However, for inputs that are tradable, such as global health commodities (e.g., testing machines and anti-viral drugs), GDP deflators or the CPI do not capture price changes. Many global health commodities demonstrate decreasing prices over time. For these tradable goods, where feasible, commodity-specific price changes should be used.

There is a specific issue when adjusting costs over time and currency as to whether one first converts the local currency to U.S. dollars and then inflates, or vice versa, as this may make a substantial difference to the estimates. For non-tradable local goods, it is preferable to inflate local currency and then convert. Conversely, for tradable and often globally purchased and priced goods (where current prices are not available), it is preferable to inflate using the US dollar GDP deflator and then convert into local currency.

Shadow prices have two related meaningsh. The one used here describes the assignment of a price where there is no market price paid for an input. One common area in global health costing requiring shadow pricing is for donated inputs, such as contraceptives, and volunteer time. Likewise, some inputs may be partially subsidized. For example, ISPOR guidelines state the drugs costs should include rebates and other drug price reductions79. Regulatory requirements may also distort drugs costs80.

For economic evaluation and other ‘economic’ rather than financial analyses, shadow prices are important as they can help capture opportunity cost. In most instances, the use of shadow prices will involve adjusting the price paid to reflect the opportunity forgone, often using a hypothetical market price.

Likewise, there is an opportunity cost of family and community members’ time for the provision of health care. In some cases, this may be forgone leisure time, but time may also be forgone for other productive activities such as housework, where there is no formal wage. For these costs, there are several approaches to estimating the value of lost productivity with different theoretical and conceptual bases (e.g., human capital vs. friction costing81). Depending on the approach, the value applied can use occupational and gender-specific wages, or equal replacement wages. Each of these can produce quite different estimates, and therefore the methods used should be made transparent82. In many LMICs the extent of informal sector employment and reporting of official wage rates can mean that appropriate estimates may be unavailable. In some cases, the method of valuation includes normative aims, such as ensuring the equal valuation of time between men and women within a household.

For economic costs, the prices of donated or subsidized goods need to be adjusted to reflect opportunity (economic) cost, often using market prices paid by other consumers, or if tradable goods international prices can be used. The valuation of donated or subsidized goods should, where practical, be based on an average of multiple estimates of local market prices; purchase price paid by the donator; or if neither of these approaches was used, an alternative approach should be described.

Where shadow pricing is used for the valuation of inputs with no market prices (volunteer time, household time), goods and volunteer time should be valued at a minimum according to a proxy or hypothesized market value (e.g., local economy/domestic service wage rates), and the method should be described. Valuation may also include normative adjustments, and these too should be explicated.